It is the year 1298. A sailor from Venice named Rustichello is in a jail in Genoa, listening to incredible stories from a fellow prisoner. Rustichello and the other man were captured in a sea battle between Genoa and Venice, two Italian city-states at war over control over trade routes in the Mediterranean Sea. The other prisoner described a twenty-four-year journey, during which he worked for a rich and powerful ruler in a faraway land we now call China.

Before he went to sea, Rustichello was an experienced writer of romance novels, so he was perfectly suited to compile the stories of his fellow prisoner. And he did so in a book he called Description of the World. It is better known, however, as the Travels of Marco Polo.

Marco Polo reported that his great adventure began shortly after meeting his father— Nicoló—in 1269. They met for the first time when Marco was fifteen years old. Nicoló Polo and his brother Maffeo were merchants from Venice. The Polo brothers often traveled to the grand city of Constantinople (now Istanbul, Turkey), where they traded goods with merchants from many Mediterranean and Black Sea ports.

Marco_Polo

Marco Polo (1254 – 1324) claimed to have traveled the Silk Road in the thirteenth century. A book about his adventures introduced Europeans to China and the cultures of the Silk Road.

Marco’s father and uncle had been away from home for young Marco’s entire life because they continued east from Constantinople to trade in markets along the Silk Road. The Silk Road was a network of trade routes that connected Europe and the Middle East with China. When the brothers attempted to return to Venice, they found a conflict between two local warlords blocking their route.

Instead of returning home, the Polo brothers accepted the invitation of a Mongol governor to travel east to meet Kublai Khan, the king of all Mongols, in his palace in faraway China. Their journey lasted three years.

Kublai Khan ruled a vast and rich land unknown to all but a few Europeans. He was impressed with Nicoló and Maffeo and the stories the brothers told of their Christian faith. The Mongol ruler asked the brothers to return to his palace with 100 Christian scholars and oil from a holy lamp in Jerusalem. The brothers told the great Khan that this oil would have magic healing powers.

Kublai_Khan2

Marco Polo (1254 – 1324) an Italian merchant from Venice whose travels are recorded in a book that introduced Europeans to China and the cultures of the Silk Road.

The Khan gave the brothers a golden tablet to present along the way. The tablet announced that the brothers represented the great Mongol ruler and were guaranteed his protection on their dangerous journey home.

Nicoló and Maffeo Polo returned to Venice to prepare for a second journey to China, but this time they took along Nicoló’s son, Marco. Before leaving, the Polos visited Pope Gregory, the head of their church. The Pope gave the Polos many gifts to deliver to Kublai Khan, but instead of the 100 scholars, Gregory sent only two friars.

At the time of Marco Polo, friars were members of the clergy, but friars did not share the status or education of a priest. A friar was addressed as “brother” while a priest was called “father.” The friars began the journey with the Polos, but when they saw the dangers they faced on the Silk Road, the representatives of the pope returned home.

Tablet_for_Polos

Kublai Khan presented the Polo brothers with a golden tablet when they left China for the first time in 1266. The tablet guaranteed the protection of the Mongol ruler on their journey home.

Rustichello wrote that the Polo’s four-year journey across the Silk Road provided Marco with first-hand experience of the many cultures of the Middle East and Asia. Finally, they arrived once again at the palace of Kublai Khan, who Marco described as “the greatest lord the world had ever known.” Kublai Khan’s palace was surrounded by walls that were four miles long. The palace was decorated with gold and silver, and the walls were adorned with beautiful pictures.

Kublai Khan did not trust many of his Chinese advisors, so, according to Rustichello’s book, he sent Marco to govern a Chinese city for three years. While in China, the Polo family became rich by trading in jewelry and gold.

Marco Polo claimed Kublai Khan would not allow the Polos to return home for seventeen years. Finally, in 1292, an opportunity arose when Kublai Khan asked the family to escort a young woman to Persia to be the bride of one of Kublai’s nephews. Persia was an ancient kingdom far west of China, but nearer to the Polos’ home in Venice.

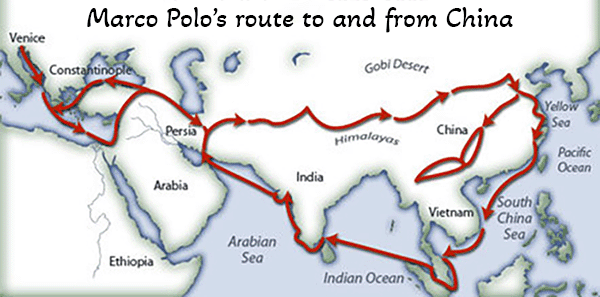

The Polo family traveled from Venice to China along one of the many routes of the Silk Road. Their return home was mostly by sea.

Marco Polo reported that thirteen ships carrying six hundred passengers left the palace of Kublai Khan, but by the time the party reached Persia, only eighteen passengers remained alive. The Polos also learned that Kublai Khan’s nephew had already died when they arrived. After leaving Persia, the Polos returned home to Venice in 1295—ending a journey that had lasted twenty-four years.

Soon after the Polos returned home, Venice went to war with the rival city-state of Genoa. Marco Polo went to sea to protect his city, but he was captured by Genoa and put in prison where he met Rustichello.

Christiasn_friar

In the thirteenth century, friars were Christian clergymen, but they generally did not share the same status as priests. Pope Gregory assigned two friars to accompany the Polo family on their 1271 voyage to China, but the friars abandoned the Polos when they realized the dangers of the Silk Road.

Rustichello wrote Description of the World before the invention of the printing press, so copies were made by hand. The book delighted its readers and stimulated interest in China and the cultures along the Silk Road. Christopher Columbus owned a copy and studied it closely before beginning his journey in 1492 to what he thought would be China.

Some observers saw Marco Polo as an astute observer with a keen memory. Some of his most fantastic claims are easy for us to understand today. Marco Polo described paper money, unknown in Venice, but which had been used by the Chinese for over a thousand years. He described a spring that gushed a stream of oil. The oil was said to be tasteless but good for burning. Marco may have been describing petroleum, or crude oil, now used to make gasoline, plastic, and other products.

613greatwall2

Marco Polo never mentioned seeing the Great Wall of China.

Others argued that Marco Polo made up his stories based on gossip and stories he heard. After all, Marco Polo reported seeing unicorns and gave a first-hand description of a battle that occurred years before he left Venice. Marco failed to mention the Great Wall of China, tea, or rice. The Chinese have no records of the Polo family, so it is unlikely Marco could have been a governor.

Many people described Marco Polo’s book as Il Milione (“The Million”) for they claimed that it contained a million lies. As an old man, Marco was asked if he invented the stories in his book. His answer was that he barely told half of what he saw.

Resources

Download this lesson as Microsoft Word file or as an Adobe Acrobat file.

View a Powerpoint presentation of this lesson.

Listen as Mr. Dowling reads this lesson.

Lexile Measure 1160L

Mean Sentence Length 18.50

Mean Log Word Frequency 3.44

Word Count 1012

Mr. Donn has an excellent website that includes a section on China.

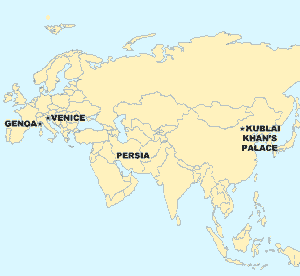

Eurasia_map_Marco_Polo

Today it is possible to fly from the Polo's home in Venice, Italy to the site of Kublai Khan's place in less than twelve hours. The Polo family's journey first journey to China took three years.