The Incas lived high in the Andes, a mountain range along the western edge of South America. They lived without horses, iron tools, the wheel, or writing. But in less than 100 years, they built spectacular cities of stone and ruled over millions of people.

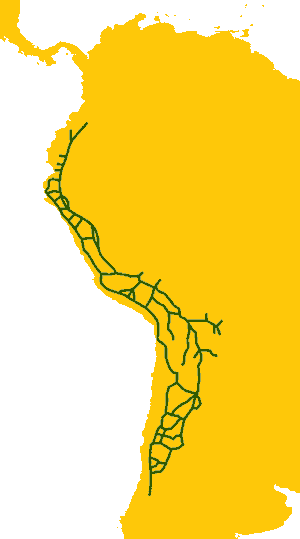

By 1491, the Incas controlled an area that stretched more than 2500 miles from north to south, but in some places no more than fifty miles from east to west. It included perhaps ten million people. At its height, the empire of the Incas rivaled the Mongols, the Romans, and Alexander the Great.

The Incas adapted to life in the Andes. The climate of their empire ranged from frigid cold to desert or tropical, often within a few miles due to the steep, rocky slopes of the Andes.

The empire included speakers of over 100 languages, but Inca rulers spoke Quechua (pronounced KEH-chuh-wuh), still the speech of 8 to 10 million people in the mountains of Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador.

Although the Incas did not know how to use iron, they crafted great cities using only stone tools. Inca engineers constructed walls with huge blocks that fit together without the use of mortar. Despite the volatility of their earthquake-prone empire, many Inca buildings remain standing today.

Inca_bridge

The Incas crossed canyons and rivers with swinging bridges constructed of rope.

Some of the empire’s most impressive buildings were in Cusco, the Inca’s capital city. Four wide gateways in the city led to an enormous raised plaza at its center. The center was carpeted in white sand carried up the Andes from the Pacific Ocean and raked daily by workers. The walls surrounding the plaza were cut from enormous blocks of stone crafted so finely that one explorer said, “the point of a pin could not have been inserted in one of the joints.” Cusco means “navel,” for the Incas believed their capital was the center of the world and the sacred home of their gods.

The Inca’s greatest engineering achievement was a network of more than 14,000 miles of roads and bridges. Relay runners called chasquis (pronounced CHAH-skis) were trained to carry messages from the emperor to their furthest reaches of his realm.

Chasquis needed to have strong minds and strong legs. The Incas did not have writing, so each runner would have to memorize his message and immediately run to the next station.

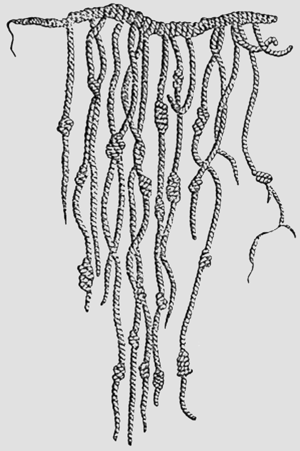

quipu

The “talking knots” the Incas called Quipu. Camayocs were Inca officials charged with reading quipus. The camayocs stored a vast collection of quipus in pottry jars in the Inca capital at Cusco.

Some chasquis carried quipo, (pronounced KWEE-po) lengths of different colored knotted strings tied to a central cord. Inca rulers used the “talking knots” to record who paid taxes, how often roads were maintained, and where troops were stationed. The chasquis delivered the messages, but only specially trained scholars understood the meaning hidden in the colors and weaving of this mysterious system.

Though the roads were well maintained, the chasqui had to run up and down the steps of mountains. The Incas had no use for the wheel because they lacked strong animals capable of pulling a cart or plow.

The largest animals the Inca knew were llamas —distant relatives of the camel. Although llamas can carry only a small amount of weight on their backs, they are nimble enough to navigate the steps of the Inca road system.

The Incas crossed canyons and rivers with swinging bridges constructed of rope. Inca engineers developed a canal system and built huge cisterns to hold water for the dry seasons.

711incaroads

The Incas built a transportation network of more than 14,000 miles of roads and bridges.

The Incas crossed canyons and rivers with swinging bridges constructed of rope. Inca engineers developed a canal system and built huge cisterns to hold water for the dry seasons.

Inca farmers cut strips of level land called terraces into the mountains. The terraces provided the Incas with flat surfaces to grow peppers, squash, peanuts, and corn. The forbidding climate forced the Incas to rely heavily on root vegetables such as potatoes and manioc. Manioc is also known as tapioca.

The lack of large animals limited meat in the Inca diet, but they hunted deer, llamas, ducks, and guinea pigs. The Inca road system made it possible to transport fish from the Pacific Ocean to villages high in the Andes.

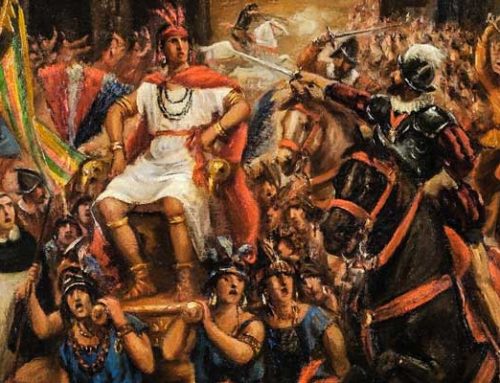

Spanish conquistadors vanquished the Incas in 1533. In the years that followed, Spain imposed laws forbidding local customs. They required the Incas to adopt Spanish customs and clothing. Resistance from the Andes continued for centuries. Today, Spanish is the primary language of western South America, but in 1993, the Constitution of Peru declared Quechua—the language of the Incas—also to be official.

Llama

The South American llama is genetically related to the camels of the Middle East and North Africa. They have been used as a meat and pack animal for hundreds of years.

Resources

Download this lesson as Microsoft Word file or as an Adobe Acrobat file.

Lexile Measure 1130L

Mean Sentence Length 16.61

Mean Log Word Frequency 3.32

Word Count 681

Mr. Donn has an excellent website that includes a section on Native Americans.

inca_terrace

The Incas has to create flat land to farm, so they made terraces. The steps of the terraces allowed the Incas to grow peppers, squash, peanuts, and maize.