When the Spanish conquistadors arrived in Mesoamerica, they learned of the rich and mighty Aztecs, the most powerful civilization in the New World. The Aztec capital was Tenochtitlan (pronounced te-noch-tit-lan), a city of more than 200,000 people filled with gold and silver. At the center of Tenochtitlan stood a towering pyramid topped by temples for the Aztec gods of the sun and the rain. Palaces for wealthy Aztec nobles surrounded the pyramid. Their great wealth and power obscured the fact that the Aztecs hid even from themselves: not long before, they were a desperately poor nomadic people who wandered into the land that would become their home in the Valley of Mexico.

The Aztecs trace their history to Aztlán (pronounced ahz-LAHN), an area north of the Central Valley of Mexico, perhaps in what is now the southwestern United States. The Aztecs called themselves the Mexica (pronounced ma-SHEE-ka), a name from which Mexico is derived. The term Aztec means “person of Aztlán.” It was first used in the nineteenth century to distinguish the modern people of Mexico from the ancient civilization.

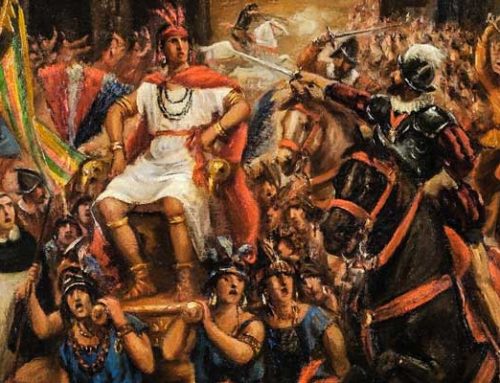

Moctezuma

Moctezuma Xocoyotzin (the Younger) ruled the Aztecs when the mighty empire fell to Hernán Cortés in the sixteenth century.

When the Aztecs arrived in the Central Valley of Mexico about 1300, their neighbors scorned them. The people of the valley considered themselves to be the proud descendants of the Toltec people, while they viewed the Aztecs as savage, uncivilized drifters.

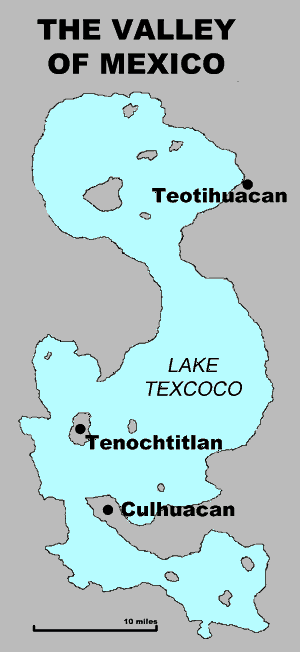

The Aztecs wandered around the valley until the King of Culhuacan (pronounced kool-wha-kan) allowed the Aztecs a permanent home in exchange for working as mercenaries. Mercenaries are soldiers hired to fight for a living. The Aztecs also worked at lowly jobs that other people rejected. As time passed, the Culhuacan people began to respect the hard work and brutal fighting skills of the Aztecs.

The Aztecs roamed the shores of Lake Texcoco in the Central Valley of Mexico before settling on an island in the lake.

In 1323, the King offered his daughter in marriage to the Aztecs, thereby inviting them into his royal family. The Aztecs sacrificed the Culhuacan princess to Huitzilopochtli (pronounced wete-see-o-POK-ta-lee), their bloodthirsty god of war. The enraged king expelled the Aztecs, forcing them once again to wander the Central Valley of Mexico.

The Aztecs lived in a land of earthquakes that caused great destruction. Their legends said the gods destroyed and recreated the world over and over. They believed that the world would be destroyed once again if they did not satisfy their gods by providing them with human sacrifices.

An Aztec priest had a vision that they should build their new home at a place where they found an eagle sitting on a cactus with a snake in its mouth. After two years of wandering, the Aztecs found that unique vision on a small island in the middle of Lake Texcoco, so they waded into the shallow lake to build their new home. The image of the eagle, cactus, and snake are part of the flag of present-day Mexico.

The Aztecs created farmland in their new home by constructing a series of artificial islands called chinampas. They marked off small areas with poles and clay walls, then filled the space with muck taken from other parts of the lake, leaving enough room for canoes to travel between the islands. The surfaces of the chinampas were fertile land that provided the Aztecs with as many as seven harvests a year.

In 1427, the Aztecs formed a secret agreement with two other kingdoms. This Triple Alliance conquered the other cultures of the valley and forced them to pay tribute, or payment for protection.

When they gained control of the Central Valley of Mexico, the Aztecs rewrote history to hide their humble origins. Tlacaelel (pronounced tlak-ah-lel) was the half-brother and closest advisor of Aztec King Moctezuma I. Tlacaelel ordered all old history books burned so there would be no memory of who the Aztecs once were. Tlacaelel’s new history said Huitzilopochtli chose the Aztecs to rule the valley. By erasing history, the Aztecs made their transformation complete. They had gone from peasants to princes.

The Aztec Chronicles

We know more about the Aztecs than any other pre-Colombian civilization primarily because of the reports of two soldiers and two priests. Their accounts occasionally contradict one another, but taken together, along with the recollections of other writers, we have a good idea of what life was like in the Central Valley of Mexico when the conquistadors arrived in 1518.

Hernán Cortés was the captain who defeated Tenochtitlan. He wrote several letters to the King of Spain that provided detailed descriptions of people, places, and events. Cortés’ letters provide insight into the Aztec culture at the time of first contact, but his motivation perhaps makes his writing suspect. The Spanish governor of Cuba forbade Cortés from sailing to Mexico and sent a force to stop him. Cortés may have exaggerated Aztec barbarism to justify his destruction of the Aztec capital. Cortés portrayed himself as the hero of the Aztec conquest, but thirty years later, one of his soldiers told a different story.

Bernal Díaz wrote The True History of the Conquest of New Spain, a lively account describing Aztec cities and their people. Like many of the conquistadors, Díaz felt that Cortés took more than his share of the wealth from the Aztec treasury.

Unlike Cortés and Díaz, Bernardino de Sahagún spoke Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs. Sahagún was a priest who spent fifty years traveling the Central Valley and chronicling Aztec life. His twelve-volume Florentine Codex is an encyclopedia of the Aztec world. Sahagún had respect for the indigenous people and a distinct dislike for the conquistadors.

Another priest, Diego Durán, was born in Spain but was raised in Mexico. He was sympathetic to the Aztec people and outraged at their culture’s destruction. Durán gained the confidence of the Aztec people and was able to witness and record many Aztec rituals.

Resources

Download this lesson as Microsoft Word file

or as an Adobe Acrobat file.

Lexile Measure 1010L

Mean Sentence Length 14.97

Mean Log Word Frequency 3.43

Word Count 464

Mr. Donn has an excellent website that includes a section on Native Americans.

Moctezuma

Moctezuma Xocoyotzin (the Younger) ruled the Aztecs when the mighty empire fell to Hernán Cortés in the sixteenth century.