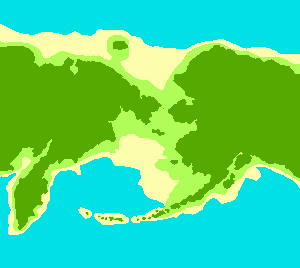

Over thousands of years, humans spread from Africa to Europe and Asia. Long before the invention of farming, the wheel or writing, the first hunters reached Beringia. Beringia is a modern name for a strip of land that once connected Asia to Alaska in North America.

The current evidence suggests that the first humans crossed this “land bridge” at least 20,000 years ago and perhaps even earlier.

The Bering Strait has separated Asia and America for about 15,000 years. The continents are now more than fifty miles apart, but at one time, they were connected by a passage more than 1000 miles wide.

Beringia_coastline_map

The coastline of Beringia during the last Ice Age.

Beringia existed during the last Ice Age, a period when the earth’s climate was colder. During an ice age, precipitation that fell on land would harden into large masses of ice called glaciers. As ocean waters accumulated in glaciers, sea levels fell about three hundred feet.

Scientists fear modern industry has made the earth warmer, causing polar ice to melt. These melting ice caps could cause the oceans to rise and submerge coastal lands.

Although the climate of Beringia was frigid, it appears to have been warmer than the nearby land is today. Beringia was not covered with ice because there was very little snowfall in the region. Instead, Beringia was covered with grass and small trees that fed large mammals such as bears, bison, and the now-extinct wooly mammoths and mastodons. These animals attracted human hunters to the region. The hunters who crossed Beringia into America came in small groups beginning about 40,000 years ago.

The glaciers melted as the earth grew warmer, causing the land bridge to slowly close about 15,000 years ago—at least 9000 years before civilizations developed in Egypt, Mesopotamia, and China. Today more than 50 miles of ocean separates Asia from North America.

Some scientists believe the first Americans could have arrived by sea, following the coastline of the Pacific Rim of northeastern Asia and Beringia to as far south as South America. They suggest the waters of most of the route contained forests of edible seaweeds called kelp. In addition to being nutritious, kelp supports fish and other sea life that could have sustained early explorers. It is difficult to prove the “kelp highway” theory correct because rising sea levels would have submerged any evidence left behind by the explorers. Still, it might help to explain ancient skeletal remains found primarily in South America that do not fit the profile of the people who passed through Beringia.

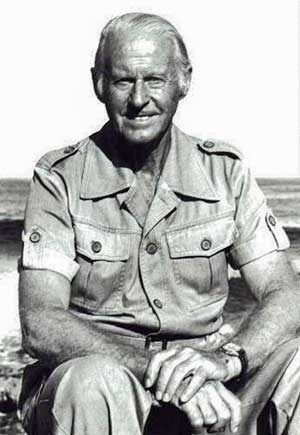

Another theory suggests that there may have been some migration to America from the Polynesian Islands of the Pacific, possibly by sailors who were blown off course. In 1947, adventurer Thor Heyerdahl constructed a raft using ancient technology. Heyerdahl and a crew of six sailed 3770 miles on the Kon-Tiki, named after an Inca god. Their 97-day journey took them from Peru to the island of Puka Puka. Heyerdahl’s voyage proved that ancient sailors could travel the Pacific Ocean, but not that it actually occurred.

Kon-Tiki

Kon-Tiki was the raft used by Norwegian explorer and writer Thor Heyerdahl in his 1947 expedition across the Pacific Ocean from South America to the Polynesian islands.

The Inuit—traditionally known by outsiders as Eskimos—also reached America from Asia, but long after the land bridge had closed. The Inuit crossed the frigid waters of the Bering Strait in boats between 6000 and 2000bce. Their DNA indicates that the Inuit are genetically unrelated to the other indigenous people of America.

occurred.

Resources

Download this lesson as Microsoft Word file, a Google doc, or as an Adobe Acrobat file.

View a Powerpoint presentation of this lesson.

Listen as Mr. Dowling reads this lesson.

Thor_Heyerdahl

Norwegian adventurer Thor Heyerdahl (1914 – 2002) sailed 5,000 miles across the Pacific Ocean in the Kon-Tiki. Heyerdahl’s expedition demonstrated that long sea voyages were possible in ancient times.