As the power of the Roman Empire faded in the first centuries of the Common Era, worshiping the Emperor and Roman gods became less prevalent. A new faith, Christianity, developed from Judaism, a religion practiced initially in a remote outpost of the Empire called Judea.

After the death of a holy man named Jesus in about 30CE, his followers spread the message of Christianity to cities throughout the Empire. In Christianity’s early history, it was a Roman citizen’s civic obligation to honor the Emperor and the Roman pantheon of gods and goddesses. The Roman government often persecuted Christians because the Christians believed honoring anything except their one God would lead to damnation. Emperor Nero blamed Christians for starting the Great Fire of Rome in 64CE. Emperor Decius declared Christians to be “enemies of Rome.” There are stories of Roman officials ordering Christians to be thrown to wild beasts for refusing to renounce their faith. Despite Roman authorities’ efforts to suppress it, Christianity continued to grow.

Over time, many traditional Roman practices merged with Christian celebrations. Christians began to celebrate the birth of Jesus in December, when Romans traditionally celebrated the sun’s birth after the longest night of the year.

Emperor Constantine decreed that Christians could practice their beliefs without oppression in CE311. By 325, Constantine called Church leaders to a meeting in Nicaea, in present-day Turkey, to standardize Christian teaching throughout the Empire. Forty-three years after Constantine’s death, Emperor Theodosius declared Christianity to be the Empire’s official religion. The standards set by Constantine at Nicea were to be considered official, and all other Christian teachings were heresy. Heresy is a belief that contradicts or defies established religious teachings.

Paul_of_Tarsus

Paul the (c. 5CE – c. 60CE) commonly known as Saint Paul or Saul of Tarsus spread the message to Christianity to cities in Europe and Asia Minor.

Because Christianity had developed independently in cities throughout the Empire, there was a diversity of beliefs among the faithful. After Nicean Christianity became the Empire’s official religion, people who practiced heretical beliefs often faced punishment or death.

Christianity spread past the borders of the Roman Empire to barbarian lands. The faith spread to present-day France after Frankish king Clovis I became a Christian in 496. By the seventh century, missionaries spread their beliefs to Great Britain, the last outpost of Western Europe to accept Christianity.

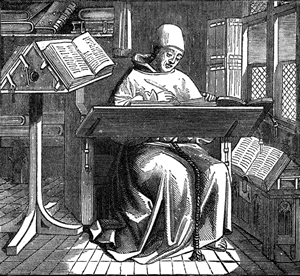

Religious life was often the only way to get an education in Europe during the Middle Ages. It also allowed poor people to escape a dreary life and possibly rise to power. Some Christians renounced their possessions and lived apart from the rest of society. Men lived as monks in monasteries and women as nuns in convents. A fifth-century monk, now called St. Benedict, established strict rules for monasteries, including when monks should eat, pray, and work. Often the younger sons of nobles or widowed women would leave the stress of everyday life for the care and comfort they found in monasteries and convents.

Christian_monk_during_Middle_Ages

Some Christian monks would spend their working time in a scriptorium, a place within a monastery set aside for copying manuscripts and illustrations by hand.

Monasteries produced many well-educated men prepared to serve as administrators for uneducated kings and lords. Some Monks copied books by hand in an era before the printing press. The Christian Bible was the only book in many smaller villages. Often the only person in a village capable of reading the Bible was a Christian priest.

People only considered Europe a particular place after the Middle Ages. Instead, they spoke of “Christendom,” or the community of Christians. Christianity was the most significant influence of the Middle Ages in Europe. Though there were a significant number of Jews, Muslims, and pagans, by 800, Christianity had become the faith of most Europeans.

Resources

Download this lesson as Microsoft Word file or as an Adobe Acrobat file.

Listen as Mr. Dowling reads this lesson.

Mr. Donn has an excellent website that includes a section on the Middle Ages.

703abby

Construction on the Cluny Abbey in Saône-et-Loire, France began in 910CE.